In this article we review the development of a UK legal framework to challenge workplace sexual harassment and the limitations of this. We also outline the extent and distribution of the issue and note recent union campaigning in the post #MeToo context.

The UK Legal Framework

For at least the last half century activists have been waging campaigns to prevent workplace sexual harassment in the UK, and to provide redress to victim-survivors. Although sexual harassment only came to be formally defined in primary legislation through the 2010 Equality Act, a key breakthrough occurred in the 1980s when judge-made caselaw defined sexual harassment under the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act (1). A particularly important case was Porcelli v Strathclyde Regional Council 1986, where Jean Porcelli, a school laboratory technician, experienced sexually abusive comments from male co-workers.

The terminology and definitions of workplace sexual harassment entered UK activist and legal discourse from the United States and focused on the two types described by Catherine Mackinnon (2): quid pro quo sexual harassment (sexual coercion through threats of retaliation or promises of advancement) and the creation of a ‘hostile environment’ (where women workers are pushed out of their jobs through degrading treatment). In these early efforts to tackle workplace sexual harassment, unions played an important, if not always a leading, role. In particular, the National Association of Local Government Officers (NALGO, now part of Unison) undertook campaigning on the issues in the early 1980s, encouraging the local negotiation of workplace policies (3).

Although this early work was important, research conducted by Louise Jackson and colleagues suggests there was a backlash against efforts to regulate and prevent sexual harassment from the 1990s onwards, as the issue became wrapped up in party politics and opposition to increasing employment regulation measures by the European Union (4).

Moreover, the current legal framework in the UK still remains premised on individuals bringing cases through the Employment Tribunals System, where they face barriers including time limits (3 months less 1 day from the date of the last act of sexual harassment), employers who generally ‘outgun’ workers in terms of access to legal representation, the biases of tribunal judges and low compensatory awards (if they are successful) (5).

It is therefore unsurprising that only 18 cases of sexual harassment were brought to Tribunal in 2018 (6) and only 23 cases in 2021(7). To put these figures in context, extrapolating from the government’s own data (8) would suggest that 9.85 million workers experience some form of workplace sexual harassment annually, ranging from sexual jokes and unwelcome staring to sexual assault, flashing, or actual or attempted rape (the respective figures for these three forms of workplace sexual harassment would be 1.36 million, 1.02 million and 680 thousand) (9). We can therefore see that this individualised system of workers seeking redress is woefully inadequate.

The Workers Protection (Amendment of Equality Act 2010) Bill 2023 introduced a mandatory duty on employers to prevent sexual harassment (10) in the workplace. While welcome, it was watered down from its first draft, excluding third party harassment and not requiring employers to take “all” reasonable steps to prevent workplace sexual harassment. The new UK government elected in July 2024 is committed to a new ‘Employment Rights Bill’, which will reinstate protections for workers from ‘third party’ sexual harassment (by clients, customers or contractors), will require employers to take ‘all reasonable steps’ to prevent it (a similar right was abolished by a previous government in 2014) and will introduce a power for the government to define what “reasonable steps” are.

Nonetheless, individuals will not be able to bring a claim, only the government regulator – the Equality and Human Rights Commission – can (11), and that agency has seen its budget slashed by two-thirds over the last decade and has no legal right to proactively inspect workplaces. It will continue to rely on workers taking claim to and winning at an Employment Tribunal for the EHRC to investigate. There is currently a labour movement campaign – End Not Defend (12) – that is lobbying for the Employment Rights Bill to make sexual harassment an obligation for the government’s health and safety regulator, the Health and Safety Executive, which is the case in other jurisdictions, including Australia and the Netherlands (13).

The Prevalence and Drivers of Workplace Sexual Harassment in the UK

In the post #MeToo era there have been a series of surveys in the UK that have demonstrated that workplace sexual harassment affects at least 29% of workers every single year, that women are more likely to face sexual harassment than men (up to twice as likely), and that other disadvantaged groups are also at increased risk of sexual harassment (minoritised ethnicities, disabled people, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people) (14).

These same surveys demonstrate that workers in particular industries are much more likely to face workplace sexual harassment, with workers at greatest risk in hospitality, personal services, construction and technology and telecoms. This is partially related to vertical (where men dominate senior roles) and horizontal (where men and women are clustered in different roles) gender segregation and the dynamics of different industries (15).

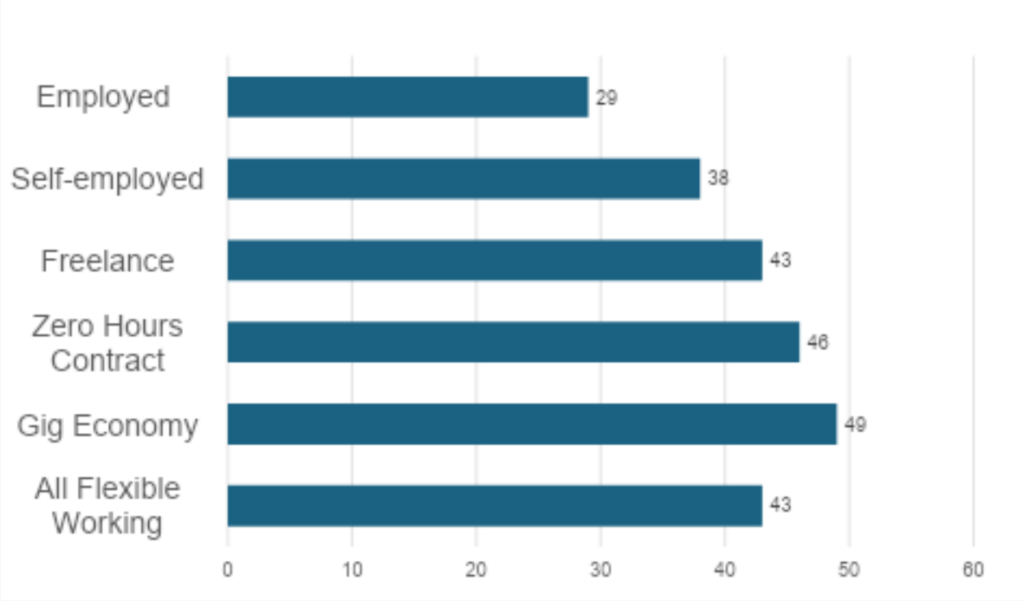

Our own research focuses on the UK hospitality industry – bars, restaurants, fast-food and hotels – and draws attention to the routine sexualisation of women workers, the reliance upon hiring very young workers who are less likely to know their rights or have less confidence asserting those rights, as well as the hiring of workers on insecure or ‘precarious’ contracts (16). The relationship between insecure contracts and vulnerability to workplace sexual harassment is starkly illustrated in a 2017 survey conducted by the BBC (Figure 1).

Union Campaigning on Workplace Sexual Harassment in the UK

Also stimulated by the outpouring of anger over #MeToo, many UK unions have seen an increase in campaigning on the issue of workplace sexual harassment. This includes the development of a comprehensive framework by the actors’ union, Equity, to challenge sexual harassment, which includes a focus on auditions and high-risk work environments (18).

Notably, the Bakers, Food and Allied Workers Union (BFAWU) and Unite the Union have waged long-running campaigns against workplace sexual harassment in hospitality. For BFAWU, this has centred on the fast-food multinational McDonald’s, where their campaigning has uncovered over 1,000 cases of workplace sexual harassment, and has led to scrutiny of the way McDonald’s deals with the issue by the media, parliament and the equalities regulator (19). BFAWU have also worked with local campaigns like Sheffield Needs A Pay Rise to combat workplace sexual harassment. In one instance this included taking direct action – a ‘march on the boss’ – to demand locks on changing room doors in a brand-name fast-food outlet, where previously older male managers had ‘accidentally’ walked in on younger female members of staff when they were getting changed (20).

Unite meanwhile have produced surveys of their hospitality membership, uncovering the extent of workplace sexual harassment (21). They have also run an innovative campaign – Get Me Home Safely – to change local licensing laws in order to make late night hospitality venues provide safe transport options home for bar workers who may face sexual harassment in the street (22).

It is clear such campaigns are helping to inspire a new generation of young trade unionists, who are often more likely to unionise over issues of disrespect in the workplace than over traditional concerns regarding pay and contracts (although these remain important).

Nevertheless, the trade union movement in the UK has in the last five years been rocked by reports of sexual harassment and ‘institutional sexism’. The unions involved have been dominated by a male leadership, have had a culture of holding meetings in places where alcohol is served and where bullying has been endemic. These reports echo similar revelations concerning trade unions in the USA (23).

There has been a long and ongoing struggle to challenge workplace sexual harassment by unions and through the courts in the UK, which has been given renewed impetus in the wake of the #MeToo movement – Weinstein after all was an employer who used his market power to perpetrate his crimes. What our research on the hospitality industry has revealed is the way in which workplace sexual harassment is linked to industry dynamics, workers’ vulnerabilities and insecure contracts. It has also showed that young workers are increasingly prepared to stand up to these issues, but they need supporting by a trade union movement that has put its own house in order.

References

(1) Jackson L Ayadab S Christoffersen A Conley H Galt F Mackay F and O’Cinneide C (2024)

‘Campaigning against workplace ‘sexual harassment’ in the UK: law, discourse and the news press c. 1975–2005’, Contemporary British History, vol. 38(2), p. 321-22.

(2) Mackinnon C (1979) Sexual Harassment of Working Women, New Haven: Yale University Press.

(3) Jackson et al (2024), p. 338.

(4) Jackson et al (2024), p. 340.

(5) Jeffery B Beresford R Thomas P Etherington D & Jones M (2024) Challenging Sexual Harassment in Low Paid and Precarious Hospitality Work, Sheffield: Zero Hours Justice, p. 99-102.

(6) Focus on Labour Exploitation (2021) Position paper: Tackling sexual harassment in low-paid and insecure work, London: FLEX, https://labourexploitation.org/publications/tackling-sexual-harassment-low-paid-and-insecure-work, p. 6.

(7) Ferreira L and Bychawski A (2022) ‘Most workplace sex harassment cases fail as Tories drag feet over reforms’, Open Democracy, 3rd of May, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/workplace-sexual-harassment-cases-tribunal-conservative-party/

(8) Government Equalities Office (2020) 2020 Sexual Harassment Survey,

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/60f03e068fa8f50c77458285/2021-07-

12_Sexual_Harassment_Report_FINAL.pdf, p. 72.

(9) It should be noted that these latter three are not only forms of ‘sexual harassment’, they are also offences under the UK criminal law.

(10) Busby N (2024) ‘The Worker Protection (Amendment of Equality Act) Act 2023: Implications for Protection Against Sexual Harassment’, Industrial Law Journal, 53(3): 505-523.

(11) Thompsons Solicitors (2024) Employment Rights Bill: Full Briefing,

https://www.thompsons.law/media/6487/employment-rights-briefing-10.pdf, p. 5-6.

(12) https://workerspolicyproject.org/endnotdefend/

(13) Riso S (2024) ‘After #MeToo: Changes in sexual harassment policy at work’, Eurofound, 1st October, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/resources/article/2024/after-metoo-changes-sexual-harassment-policy-work

(14) Jeffery et al (2024), p. 21-30.

(15) Bull A (2023) Safe to Speak Up? Sexual harassment in the UK film and television industry since MeToo, University of York, https://screen-network.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2023/10/Safe-to-Speak-Up-summary-report.pdf, p. 19-20.

(16) Beresford R & Jeffery B (2024) ‘Challenging Sexual Harassment in Low Paid and Precarious Hospitality Work’, Notes from Below, https://notesfrombelow.org/article/challenging-sexual-harassment-low-paid-and-precari

(17) ComRes (2017) BBC: Sexual harassment in the workplace 2017, https://savanta.com/knowledge-centre/poll/bbc-sexual-harassment-in-the-work-place-2017/, p. 33.

(18) https://www.equity.org.uk/advice-and-support/dignity-at-work/equity4women-toolkit/sexual-harassment

(19) Sagir C (2023) ‘“Toxic culture” at McDonald’s won’t end until it ends insecurity of casualised workers, union warns’, Morning Star, 8th February, https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/b/toxic-culture-at-mcdonald-wont-end-until-it-ends-insecurity-of-casualised-workers-union-warns

(20) Jeffery et al (2024), p. 128.

(21) Bence C (2018) ‘Not on the Menu – what the Presidents Club revealed about hospitality work and media attitudes’, Open Democracy, 1st February, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/not-on-menu-what-presidents-club-revealed-about-hospitality-work-and-media-attitu/

(22) https://www.unitetheunion.org/campaigns/get-me-home-safely-campaign

(23) Avendaño A (2025) Solidarity Betrayed: How Unions Enable Sexual Harassment and How They Can Do Better, London: Pluto Press.

-

Bob Jeffery

Bob Jeffery

Senior Lecturer in Sociology, Course Leader, MRes Social Research, Institute of Social Sciences, Sheffield Hallam University

-

Ruth Beresford

Ruth Beresford

Research Associate, Institute of Social Sciences, Sheffield Hallam University