Setting the European digital transition in motion – New evidence from Cedefop’s 2nd European skills and jobs survey

Several years before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, concerns about ensuing job losses due to automation as induced by artificial intelligence algorithms, advanced robotics and other Industry 4.0 digital technologies, were heightened. Cedefop’s first European skills and jobs survey (ESJS) had already revealed that 43% of EU adult employees were exposed to new machines and ICT systems at work. Others had cautioned that about half of all jobs in advanced economies may be susceptible to replacement by AI algorithms. In light of such evidence, many European workers are concerned; Cedefop’s second ESJS2 wave has recently revealed that four in ten EU+ (EU27 and Norway and Iceland) workers think that there is some chance they may lose their job in the next 12 months; about half of them think the job-displacing features of digital technology are to blame.

The coronavirus crisis has since accentuated the long-standing digital transformation of European enterprises, resulting in the greater uptake of digital and remote forms of working and learning. It also aggravated skill mismatch tensions at micro level, crippling training investments and feeding into sustained skill shortages.

Digitalisation can be a force for good, markedly improving workers’ job quality, or bad, fostering task automation and job insecurity, particularly in routine jobs. Cedefop’s ESJS2 aims at strengthening the evidence base underpinning EU VET, skills, digital and related policies. Surveying over 46 000 adult workers in 29 European countries, it takes a comparative perspective, collects up-to-date and scientifically sound information, and fills important knowledge gaps to make the EU’s ambitious targets on the twin transition a reality (Box 1).

| Box 1. In brief: Cedefop’s second European Skills and Jobs Survey (ESJS2) The ESJS2 is the second wave of a Cedefop periodic survey collecting information on the job-skill requirements, digitalisation, skill mismatches and workplace learning of representative samples of European adult workers. It builds on the first wave carried out in 2014. The ESJS2 aims to inform the policy debate on the impact of digitalisation on the future of work and skills, also in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Fielded in summer 2021, ESJS2 collected information about 46 213 adult workers in the EU27 Member States plus Norway and Iceland (EU+). Cedefop has joined forces with the European Training Foundation (ETF). By end 2023, the ESJS2 will have been carried out in more than 35 countries. More information on the Cedefop European skills and jobs survey (ESJS) is available on Cedefop’s webportal. Source: Cedefop |

The pandemic and digitalisation

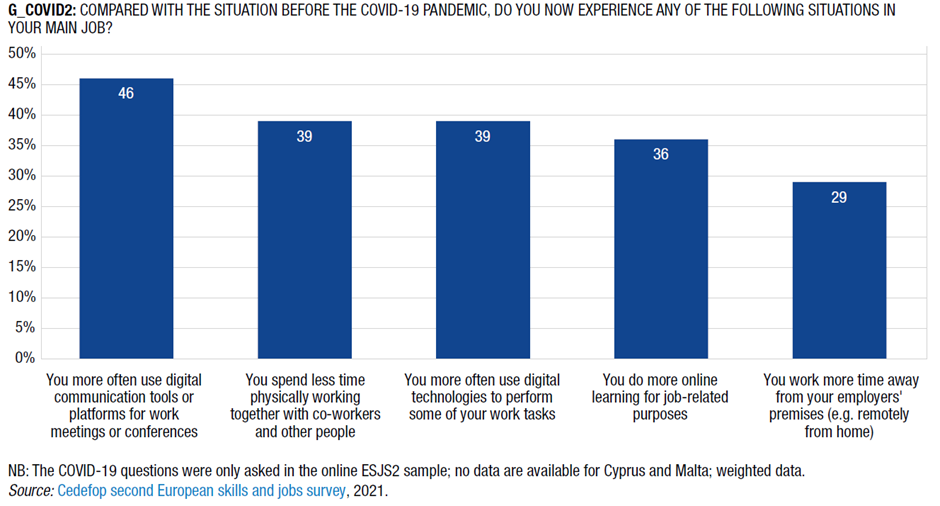

The Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the long-standing trend towards work digitalisation in EU economies. ESJS2 data reveals that compared to before the pandemic, four in ten (39%) adult workers more often used digital technology to perform some of their job tasks and three in ten (29%) worked more time away from their employer’s premises (Figure 1). Online education and training also boomed during the health crisis. About one third (36%) of EU+ workers engaged in more online learning for job-related purposes, that is six in ten of all those participating in any education and training activity during 2020-21.

Figure 1. COVID-19 pandemic and digital work and learning

Scoping digitalisation in EU labour markets

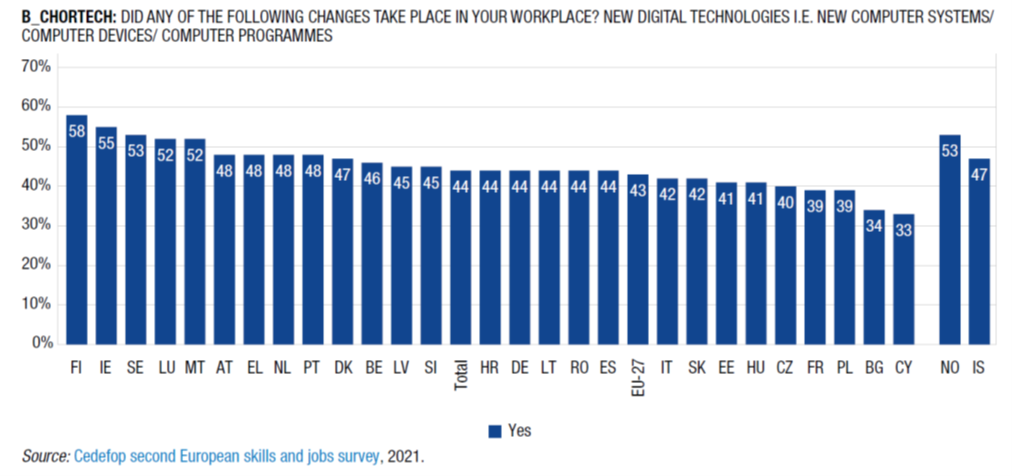

In 2020-21, almost half of adult workers saw new digital technology introduced at their workplace and 35% of them had to learn how to use it (Figure 2). This is accounted for by the one-third (32%) of European workers who had to learn new computer programs or software for their job over the period, excluding any minor or regular updates. Another 10% had to learn to use new computerised machinery for job-related purposes. The fact that such workers were more likely to be in workplaces that grew in staff size, suggests companies embracing the ‘digitalisation push’ managed to navigate the coronavirus crisis better and thrived.

Figure 2. New digital technologies in EU+ workplaces, 2020-21

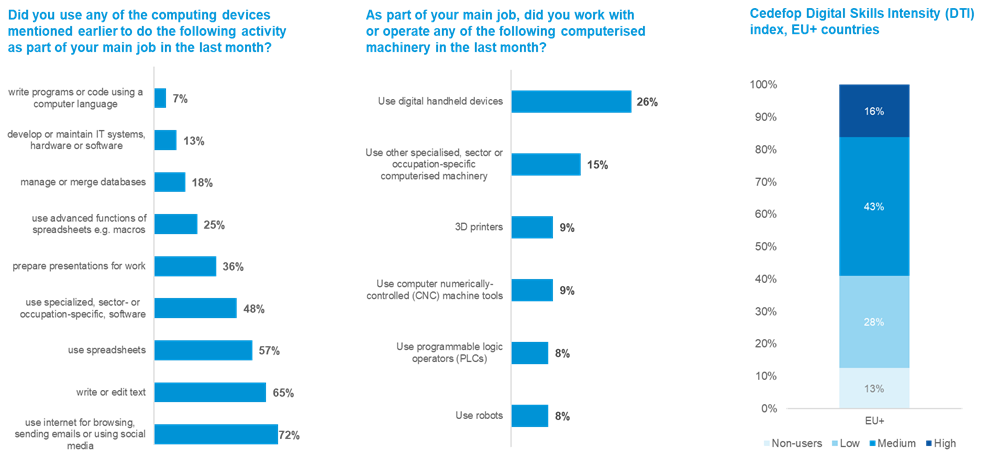

Nonetheless, while almost nine in ten (87%) adult workers use some digital device or machine to do their job, six in ten of them carry out relatively basic or low intensive digital tasks at work, or one in eight none. Although robots and 3D printers feature prominently in the popular Industry 4.0 discourse, only about 8-9% of adult workers work with or operate such technology. This highlights the significant scope to further digitalise many jobs in Europe.

Figure 3. Digital skills intensity of EU+ jobs

For many European workers, digitalisation goes hand in hand with job quality provided they have the means to up or reskill: digital jobs are less likely to be routine jobs, typically have higher autonomy and more skill development opportunities, and yield higher job satisfaction. It is important to avoid though that further digitalisation, in particular in manual occupations, results in more routine jobs where workers feel less secure. Introducing new computerised machines, such as robots, can have this effect. Workers in non-routine, analytical jobs are less affected by such negative impacts of digital technology, as confirmed by the ESJS2 analysis.

Digitalisation and EU skill mismatch

ESJS2 data reveal that 52% of EU+ adult workers need to further develop their digital skills to do their main job even better than at present – a digital skill gap, benchmarked to improved future job performance. Individuals who had to learn to use new digital technologies are more likely to have digital skills deviating from a level required for better job performance.

But many in great need of digital training, including those with changing digital job-skill demands but also digitally low-skilled workers not using computer devices at work, often do not receive it. While 45% of EU+ adult workers acknowledge they need new knowledge and skills to work with new digital technology, only one in four (26%) undertook non-formal education and training activities for the purpose of further developing the digital skills required by their job between 2020-21. Such digital skills training is mostly pursued by males and urban workers, those with higher education, in larger-sized firms and working in high-skilled occupations. Sectoral differences are also prevalent; while the training activities of more than 6 in 10 workers in the ICT sector focus on digital skills, less than 3 in 10 do so in the accommodation and food services sector.

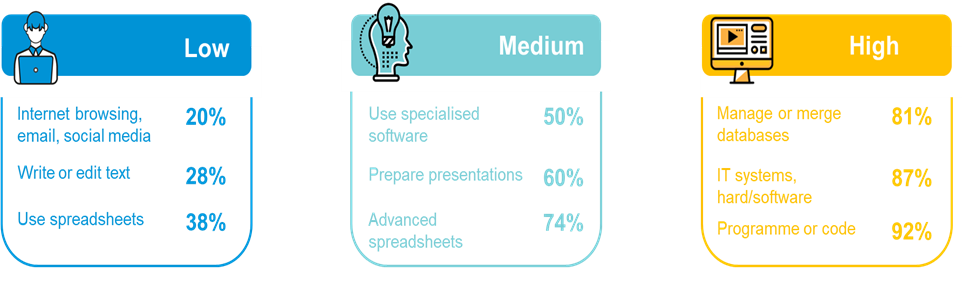

The ESJS2 evidence hence makes clear that expanding basic or mid-level digital skills training would benefit many workers. One in every five adult workers and 31% of those not using computer devices, stands to gain from training in navigating the web. 30-40% of the workforce can be further trained in fundamental word processing and use of spreadsheets (Table 1).

Table 1.Skill gaps in digital activities, EU+

The digital transformation in job markets does not only intensify skill gaps. ESJS2 data reveals that about 3 in 10 EU+ workers have qualifications that exceed the level needed to do their job – most of these overqualified workers are typically non-users of digital devices and are less exposed to learning new digital technologies at work.

Technological alarmism: fact vs. fiction

The ESJS2 also provides some insight into the extent to which popular fears of robots or machines taking away people’s job are justified by evidence.

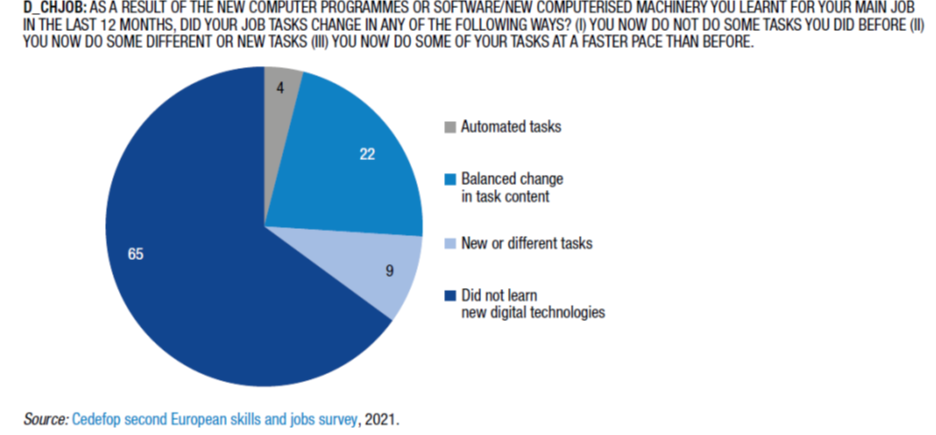

About one third of the EU+ workforce believes that new digital technologies in their company or organisation can or will do part or all of their jobs in the medium-term. 45% acknowledge the need for upskilling or reskilling due to digitalisation. However, only about 4% of the total EU+ adult workforce eventually did not have to perform some tasks they did before because of newly introduced digital technologies at work. 22% of the adult workforce, by contrast, saw both some task destruction and generation, a testament to both the positive and destructive nature of digital technology (Figure 4).

Workers affected by task automation tend to be lower-educated and typically employed in manual and low-skilled, elementary, jobs. They are mostly found in specific industries, such as agriculture, financial and insurance services and utilities. Although there will be job and task destruction by machines or robots in some labour market segments, it is hence clear that digitalisation first and foremost leads to massive upskilling or reskilling needs.

Figure 4. Digitalisation and task automation of EU+ jobs

The way forward for EU digital and skills policies

The ESJS2 evidence stresses the twin challenge EU policymakers are faced with. Tailored VET provision is required to enable those exposed to technological innovation to mitigate their digital skill gaps and any skills-displacing technological obsolescence in reasonable time. There is additionally a need for greater digital investment and reconfiguration towards new digital working methods in EU+ workplaces. Rather than solely speculating about which jobs may or will vanish, digital skills policies should aim to redress in-company managerial and workplace practices, following technology-enabled changes, to ensure positive human-machine complementarities.

VET policy should also focus first and foremost on the 1 in 8 of employed adults who do not use digital technologies at work and the non-trivial share with low use of digital technology at work. Addressing the mismatch between who needs digital training most and who gets it in EU workplaces is paramount. Policy makers should focus on expanding efforts to reach out to groups of workers most in need, prioritising lower-educated and older workers, females, people in low or semi-skilled jobs and employees in smaller-sized establishments. Another equally important priority for EU digital skills policies is to promote a human-centred and empowering approach to adopting digital technology.

Key sources

- Cedefop (2018). Insights into skill shortages and skill mismatch: learning from Cedefop’s European skills and jobs survey. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Cedefop reference series, No 106. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/645011

- Cedefop (2022). Challenging digital myths: first findings from Cedefop’s second European skills and jobs survey. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Policy brief. http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/818285

- Cedefop (2022). Setting Europe on course for a human digital transition: new evidence from Cedefop’s second European skills and jobs survey. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Cedefop reference series; No 123 http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/253954

- ESJS2 online data exploration: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/tools/european-skills-jobs-survey

- McGuinness, S.; Pouliakas, K. and Redmond, P. (2021). Skills-displacing technological change and its impact on jobs: challenging technological alarmism? Economics of Innovation and New Technology, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10438599.2021.1919517

- Pouliakas, K. (2018). Risks posed by automation to the European labour market. In: Hogarth, T. (ed). Economy, employment and skills: European, regional and global perspectives in an age of uncertainty, pp. 45-75. https://www.fondazionebrodolini.it/sites/default/files/pubblicazioni/file/q61_x_web_cor_0.pdf

- Pouliakas, K. (2021). Artificial intelligence and job automation: an EU analysis using online job vacancy data. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Cedefop working paper, No 6. http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/305373

- Pouliakas, K. and Wruuck, P. (2022). Corporate training and skill gaps: did COVID-19 stem EU convergence in training investments? EIB Working Paper 2022/07, Luxembourg. https://www.eib.org/en/publications/economics-working-paper-2022-07

-

Konstantinos Pouliakas

Konstantinos Pouliakas

Senior Expert, Department for Skills and Labour Market, European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop)