Following the onset of the global financial crisis, the Greek labour market has been severely hurt. Dramatic changes took place in the institutional framework allowing for greater flexibility while unemployment reached unprecedented levels. The employment relationship, similar to the case of many European countries, has been moving away from traditional forms (e.g. full-time, 40 hours, Monday to Friday, 09:00-17:00) to non-standard ones (e.g. part-time, work during unsocial hours etc.). Such forms thrived during the Greek debt crisis, following a series of reforms (see Livanos & Tzika, 2022a, 2022b). Non-standard or atypical employment, however, even though has benefits for the firms, often occurs involuntarily from the side of the employee, adding a precarious element to it. On top of everything, the Covid-19 pandemic has led to further deterioration of the labour market. According to a Cedefop Skills Forecast Covid-19 scenario, more than 7 million jobs are predicted to be lost, throughout Europe, and this would eventually further push towards non-standard forms of employment.

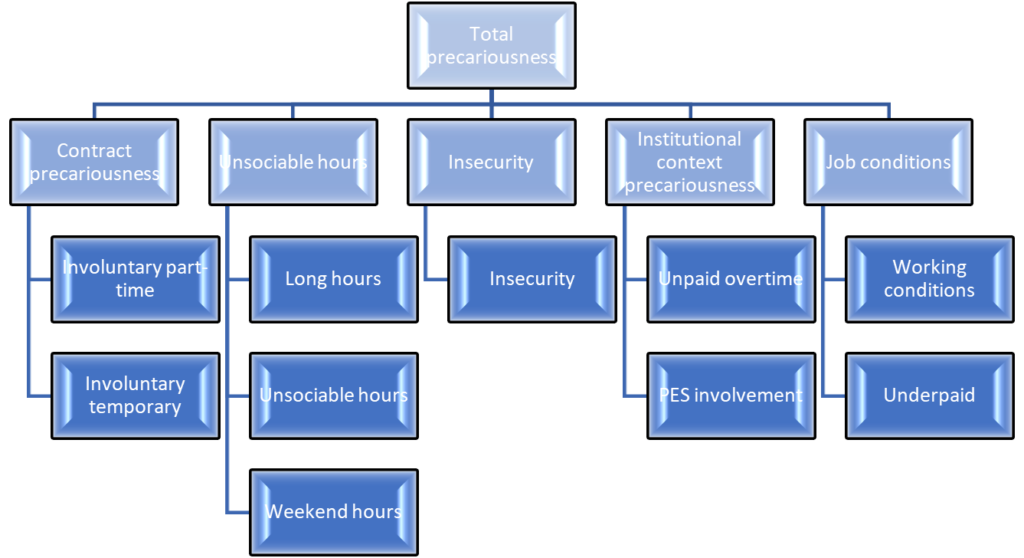

This article examines different types of precarious employment in Greece, looking into how they have evolved over a period of almost 20 years (2000 to 2018); which regions are affected the most; and which worker groups are more vulnerable to it. Precarious employment is conceived “uncertain, unpredictable, and risky from the point of view of the worker”, following the definition of Arnie Kalleberg (2009). Ten directly measurable aspects of precarious employment are examined utilising data from the EU Labour Force Survey for Greece and constructing 10 indicators. Figure 1 below displays the areas of precarious employment measured for the purposes of this article. A total precarious employment score is also provided, as a simple average of the 10 precariousness indicators, to provide a general proxy of the phenomenon.

Figure 1 Precariousness indicators categorised into five pillars

A first look at the overall score is provided in Figure 2. A score of 1 (below/above 1) means that on average everyone falls under one (less/more than one) of these categories. The higher is the score, the higher is the intensification of precarious employment. As can be seen, there is an obvious increase in 2009, after the outbreak of the global financial crisis, with precariousness being at its highest level in 2014, while never returning to the pre-crisis levels, possibly due to the long-lasting Greek debt crisis and continuous labour market reforms. In 2018, there has been a sign of relief indicated by a declining score, however, the Covid-19 pandemic is expected to further intensify the phenomenon.

Figure 2 Overall precarious employment score

Source: authors own estimations based on EU LFS data for Greece

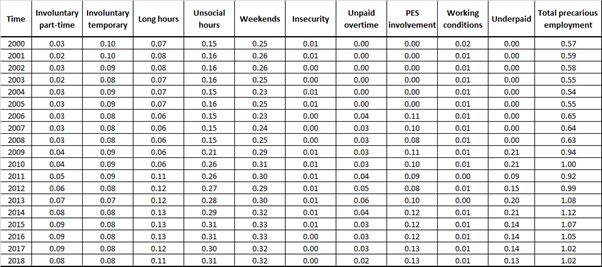

Figure 3 and Table 1 compare the individual aspects of precarious employment, as in Figure 1, for the total population. One can notice that some aspects of work worsened due to the crisis, such as working long hours or working during unsociable hours (e.g. evening, night, weekend work) with the rates of these aspects of precarity increased after 2010 and remained at high levels even until 2018, not showing any signs of recovery. A good example is our underpaid indicator (i.e. receiving pay that is less than the average of the occupation in question), which seems to have been affected the most by the crisis. In a similar vein, unpaid overtime increased in 2006, that is a few years before the beginning of the crisis in Greece, and continued increasing even more in 2012 and 2013, before showing some slight signs of recovery after 2014. This intensification of overtime work and work during unsociable hours or during the weekends, along with other adverse working conditions, may lead to several health and phycological implications for the workforce. As several studies point out, overtime work may lead to higher depression and stress rates (Kleppa, Sanne, & Tell, 2008; Luther, et al., 2017).

Figure 3 Trends in precarious employment by indicator

Source: authors own estimations based on EU LFS data for Greece

Table 1 All precarious employment indicators for the total population and the total precarious employment score over the years for the total population

Source: authors own estimations based on EU LFS data for Greece

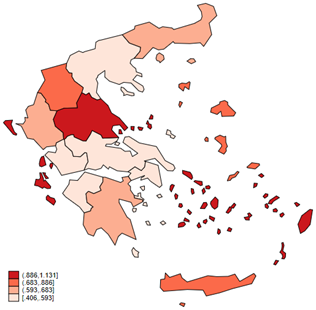

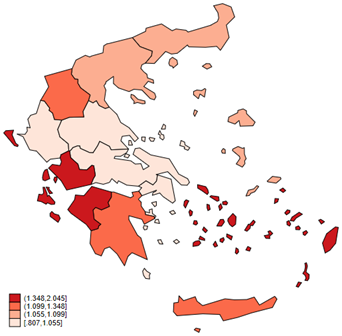

Figure 4 presents the total precariousness score per NUTS II region, all of which experienced an increase in precarious employment after 2008. Out of all the NUT II Greek regions, the Ionian Islands, South Aegean and Crete have been hurt the most after the crisis. Their common characteristic is that the economies of these regions are tourism oriented. Based on previous literature these regions have faced high consequences during the crisis, as they faced the highest fall of GDP (Petrakos & Psycharis, 2016) and are found to have the highest total involuntary non-standard employment rates in the country (Livanos & Tzika, 2022). On the other hand, the labour market of Attica is the one facing the least severe impact of precarious employment, and this is in line with the findings of previous studies suggesting involuntary non-standard employment in Attica was the least hurt by the crisis (Livanos & Tzika, 2022). Indeed, Attica is the region where half of the country’s population, is located. Hence, there are plenty of job market options in all sectors, making it easier for people to find a job and not be discouraged and easily accept precarious jobs. Figures 5-7 show the intensity of precarious employment across regions for the years 2000, 2009 and 2018 for illustration purposes.

Figure 4 Trends in precarious employment by region

Source: authors own estimations based on EU LFS data for Greece

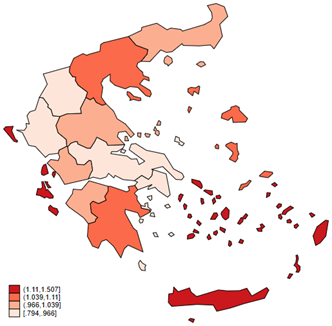

Figure 5 Total precarious employment score per NUTS II region in 2000

Source: authors own estimations based on EU LFS data for Greece

Figure 6 Total precarious employment score per NUTS II region in 2009

Source: authors own estimations based on EU LFS data for Greece

Figure 7 Total precarious employment score per NUTS II region in 2018

Source: authors own estimations based on EU LFS data for Greece

Figure 8 presents total precarious employment for the two genders. A first point to make is that both men and women exhibit the same trend over time, as precariousness is rising significantly after 2008 for both categories of workers. However, men are found to be facing higher rates of precarious work than women overall. This may be due to the role of the “breadwinner”, which is typically attributed to the man in a family, thus during crises, they have little option but to accept adverse working conditions. On the other hand, the consequences of the crisis for male workers have been more gradual compared to the consequences for the female ones. During the outburst of the crisis, between 2008 and 2010, precariousness rose more sharply for women, even exceeding the male levels, while the intensification of precariousness for men continued rising fast up until 2014. Since then, precariousness is falling for both genders.

Figure 8 Trends in precarious employment by gender

Source: authors own estimations based on EU LFS data for Greece

On the other hand, if one examines only the low-educated workers (Figure 9) the comparison between the two sexes gives a quite different picture. The low-educated women seem to be more vulnerable to precarious employment than low-educated men, especially in 2008 and 2009, at the beginning of the global financial crisis. In general, it is shown that low-educated individuals are more prone to precarious employment compared to medium- or high-educated ones. This may be the case, especially during crisis periods, as low-educated individuals may be ‘pushed’ to accept adverse working conditions in the fear of job loss.

Figure 9 Trends in precarious employment across low-educated by gender

Source: authors own estimations based on EU LFS data for Greece

All the above findings paint the picture of a labour market that has gone through continuous reforms and consecutive economic crises. Labour relations have become more flexible offering new opportunities for firms to utilise workforce. This may have significant benefits for them, however, has led to a continuous deterioration of the employment relationship. As this research has shown, other than the levels of unemployment that have sky-rocketed during the economic crisis, a new form of work, that of precarious employment, with various extensions has been created in the margins between employment and unemployment. Some regions and groups of workers may be more vulnerable than others to end up in such forms of employment. However, research has shown that precarious forms of employment such as working during unsociable hours has various negative effects on the health and well-being of the employee and can also prove to have negative effects on the firm and the economy overall (e.g. declining labour productivity). The Covid-19 pandemic and the on-going energy crisis are expected to further intensify this phenomenon as firms seek to keep only essential costs for their business continuity. The Greek labour market, which has gone through a continuous flexibilisation may be particularly vulnerable to such impacts, therefore this study is a call to action to avoid further intensification of the problem.

References

Kalleberg, A. (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American sociological review, 74(1), pp. 1-22.

Livanos, I., & Tzika, E. (2022a). Involuntary non-standard employment and regional impacts in Greece. Scienze Regionali, 21(Speciale), 39-66.

Livianos, I., & Tzika, E. (2022b). Precarious employment in Greece: economic crisis, labour market flexibilisation, and vulnerable workers. Hellenic Observatory Discussion Papers on Greece and southern Europe. GreeSE No 171

-

Ilias Livanos

Ilias Livanos

Expert in Skills Trends and Intelligence, CEDEFOP

-

Evi Tzika

Evi Tzika

Post-Doc researcher, Economics Research Centre, Department of Economics, University of Cyprus