Unless the platform economy becomes embedded in social norms about decent work, it threatens to rewrite society in its own image.

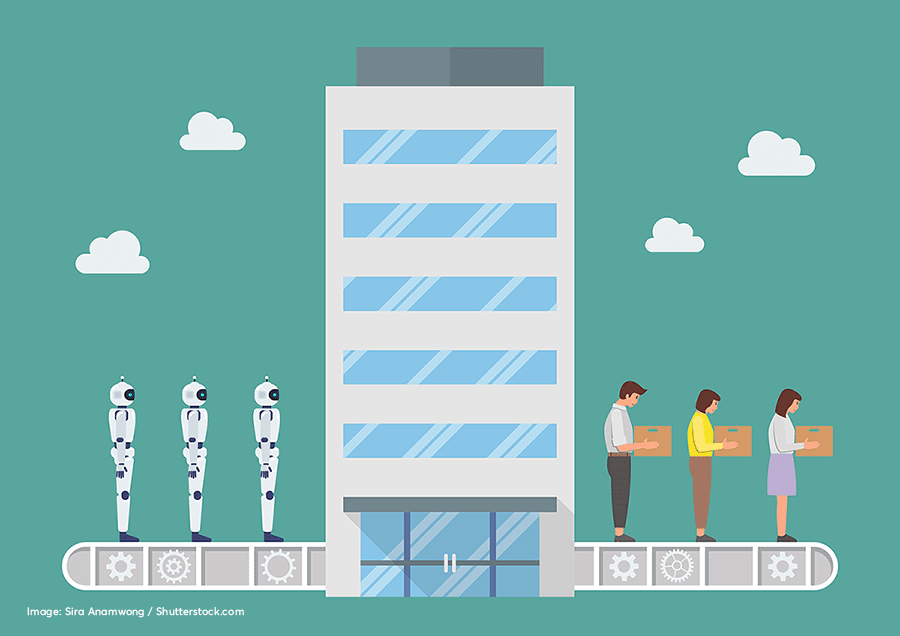

When the platform economy launched a decade ago, proponents claimed it would revolutionise the world of work. Optimistic expectations proved febrile, however, as positive stories have not taken off. On the contrary, the companies at its heart face severe criticism over inadequate employment protections (unfair work), freeriding on conventional businesses (unfair competition) and inadequate consumerprotection. A big reset is necessary, as the balance has tipped too far in the platforms’ direction.

People choose such work because they value more freedom and autonomy, digital platforms say. Yet there is strong evidencethat freedom and autonomy do not always reach their apogee there. Excessive surveillance through algorithmic controls, combined with reduced bargaining power, effectively undermines the freedom the firms tout and their workers desire.

This power imbalance is also manifest in the arbitrary way platforms act to build profit on data generated by workers for free. The companies need to manifest a compelling vision of data justice, providing fair compensation and workers’ control of the terms of their engagement with data.

Fundamental imbalances

Core to these fundamental imbalances are freeriding mindsets, embedded deep within the platform economy. Throughout the years, in markets across the globe, platforms have been benefiting from freeriding on the security provided by conventional employment.

The pandemic has further exposed this dark side. During the early lockdowns, digital platforms successfully externalised responsibilities on to governments for financial support and on to platform workers for their own protection. Some have even increased surveillance of workers during the pandemic—with the potential this will become ‘normalised’ in its aftermath.

As certain platform-type practices degrade the norms that define decent employment and responsible business conduct, we need to look at where an economy dominated by an ever-growing class of digital freeriders—and an underclass of insecure ‘freelances’—will take us. We need public debate about the limits of platform markets, reasoning together about the right ways of embedding the platform economy in the digital age, distilling what principles governing work we want to protect rather than let perish.

Such an agenda of decent digiwork would engender a robust, democratic dialogue about the moral foundations of the platform economy—with the primary goal a more equitable and engaged society, which rebalances power in digital workplaces.

Mutual interdependence

Securing decent work is above all a call for political action and social activism, recognising our shared responsibilities and mutual interdependence. As we report in a recent International Labour Organization research brief on social-dialogue outcomes reached globally during the early phase of the pandemic, there has been only a vague focus on platform workers and other groups particularly vulnerable to the impacts of the Covid-19 crisis—such as women, migrants and informal workers.

Yet vulnerability has no borders; nor has solidarity. As platform workers’ precarity has grown during the pandemic, we can no longer afford indifference to the many pariahs of the digital economy. Nor can we consume platform services without regard to effect. The evidence calls for new types of vigilance, where institutions and citizens alike have a role to play.

Mobilisation on the part of social partners—which have valuable, sector-specific knowledge—is also vital to level the playing-field, by bringing pressure for more fine-tuned regulation or by pushing digital platforms to come to thenegotiation table. This in turn makes it critical that we enable platform workers to have a voice at work.

Governments and international agencies also need to put in place effective frameworks of due diligence on labour issues, covering the platform economy, and support a formal role for labour and civil societyin these frameworks. In the case of globalised crowdwork platforms, such arrangements can lead to rebalancing power asymmetries in their cross-border operations. All these issues will soon be put on the table more intensely, as telecommuting and virtual service delivery are triggering an acceleration of the globalisation of services—in which crowdwork platforms play an important role.

Pressing platforms to adopt voluntary codes of good conduct is also important for addressing imbalances. In the long run this could bring together existing initiatives in a broader and coherent global framework, which could be actively endorsed by organisations such as the ILO and the European Union. While voluntary codes are no ‘silver bullet’ for fixing problems, they can have a more immediate impact than ‘hard’ law, which tends to move more slowly.

Transparency and justice

The time has come also to embed transparency and justice in labour markets and societies increasingly defined by data. Workers’ demands for data compensation are likely to become one of the most confrontational issues with platforms in the years to come. New trade union strategies will be needed to push forward a data-as-labour agenda, which could enable ‘data labourers’ to organise and collectively bargain with platforms. All this requires, on one hand, global trade union co-operation and, on the other, country-specific action.

Today, as the platform economy evolves, governments worldwide struggle to put in place far-reaching solutions, with international and multilateral co-ordinationweak. Considering the cross-border aspects and heterogeneity of platform work and markets, a global observatory dedicated to the platform economy could strengthen synergies and add policy coherence.

Such an observatory could be entrusted with monitoring and providing country-level support on such issues as working conditions, algorithmic management and control, or cross-border social-security co-ordination. It could be administered by an existing international institution with a strong normative labour-standards agenda, such as the ILO.

One of the most worrying tendencies of our time is the diffusion of the undesirable mindsets and attitudes that govern most platform-type work and markets—by their very DNA less equitable and inclusive—into other spheres of life, devaluing the solidarity on which democratic citizenship depends. There is no bigger challenge today than the need to offset the risk of a platform economy gradually becoming a ‘platform society’. We can still reverse this but it will take a lot of work—individual and collective.

An agenda of decent digiwork is as much about identifying the agents of transformation as it is about articulating new ideas. It is, above all else, about people and their aspirations for a future of work which takes a big turn for the better.

This is part of a series on the Transformation of Work supported by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung

Maria Mexi

Source: Social Europe

-

Maria Mexi

Maria Mexi

Consultant at the International Labour Organization (Geneva) advising on issues of digital work, and Director of Research Programmes at the Graduate Institute—Albert Hirschman Centre of Democracy and the University of Geneva, Special Adviser on Labour and Digital Economy Issues to the President of the Hellenic Republic.