Dr Chrysa Paidousi

03/12/2020

Apart from a major, ongoing health crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic is also causing a social and economic one. The restrictive measures imposed to curb the spread of the virus are creating unprecedented conditions in the job market globally, with unforeseen consequences for the future of employment and the prosperity of millions of people, mainly those with precarious employment. Women are more likely to find temporary, part-time or precarious employment than men and, subsequently, are more vulnerable to shocks in the job market.[1] This text attempts to take a first look at how female employment progressed in Greece during the time when the first social distancing measures were implemented, meaning from April to June 2020, using data from two main sources: the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) and the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound).

General trends in employment

No job losses were recorded for women from April to June 2020. Specifically, the rate of employed women aged 15 and over among all employed individuals was 42.4% in Q2 2020 from 42.2% in 2019, continuing its small yet steady upward trend since 2008[2] (39.6%). Of course, despite this positive development, the employment divide between genders continues to be quite high, reaching 15 percentage units in 2020. The unemployment rate for women also remains quite higher than men, at 19.9% (from 20.9% in 2019) and 14.1% (from 13.7% in 2019) respectively. However, in Q2 2020, and while the country was practically on full lockdown, it recorded the lowest difference in unemployment rates between genders since 2008, reaching 5.8 percentage units from 7.2 for the corresponding period in 2019 and 6.2 in 2008.

The small impact of the measures against the pandemic on the general employment rates of women (and men) can primarily be attributed to the fact that the Greek government had announced and implemented support measures for businesses and employees during that period, which resulted in suspension of employment contracts[3] rather than dismissals.[4] Furthermore, during the first phase of the restrictive measures, and despite the grim forecasts for the summer tourism season, there was a glimmer of hope for a feeble yet prolonged tourism season.

However, a key factor in containing the unemployment rates was also the small rise in employment in professions that were placed at the frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, such as doctors and nurses, cleaning staff, catering staff, and other activities, including education, which gathers a large number of female employees. For example, it is mentioned that for financial activity “Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles”, which records the highest rate of employees, the employment rate for women rose from 17.56% in 2019 to 18.7% in 2020 (Q2).[5] “Education”, a financial activity that gathers the second largest percentage of female employees, rose from 12.84% to 13.4% during the same period. Furthermore, in “Human health and social work activities”, activities that are extremely crucial and necessary during the pandemic, there is a slight rise in the employment rate, from 10.2% (2019) to 10.7% (2020).[6] Lastly, note that in “Agriculture, forestry and fishing”, the employment rate for women remained at the 2019 levels (10-11%).

The largest drop between 2019 and 2020 (Q2) was recorded in the female employment rate for “Accommodation and food service activities”, by around 2.7 percentage units. This sector suffered the most job losses in general, taking into account not just the jobs lost during that period, but also those that were not created for seasonal staff in view of the summer season.

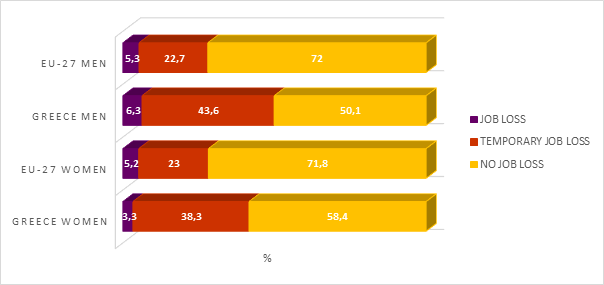

The limited loss of jobs for women during the first phase of the pandemic is also reflected in the Eurofound survey[7] for the April-May period. The percentage of men who reported that they had lost their job “permanently” was almost double (6.3%) that of women (3.3%), while the percentage of men who reported “temporary loss” was also higher than that of women by 5 percentage units. However, the rates of men and women in Greece who answered that they had not lost their job were quite lower compared to the corresponding European rates. Specifically, the rate of women in Greece who reported that “they have not lost their job” was close to 58.4%, as opposed to 71.8% in the EU-27, and the corresponding rate for men was 50%, as opposed to 72% in the EU-27.

Figure 1: Job or contract loss, by gender, April-May 2020

Source: Eurofound (2020), Living, working and COVID-19 dataset, Dublin, http://eurofound.link/covid19data.

Uncertainty about the future and drop in working hours

The Eurofound survey findings reveal another difference between men and women in Greece, which relates to their current uncertainly as to their future employment status. In Greece, men appeared more insecure (oddly enough) compared to women as to losing their job in the next three months.

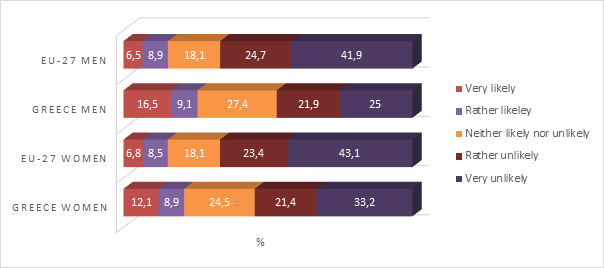

Figure 2: Fear of job loss in the next 3 months, by gender, April-May 2020

Source: Eurofound (2020), Living, working and COVID-19 dataset, Dublin, http://eurofound.link/covid19data.

Specifically, 16.5% of men consider it “very” likely to lose their job and 9.1% “rather” likely, while the corresponding rates for women are 12.1% and 8.9%. However, comparing these rates to the corresponding EU-27 averages demonstrates that Greek men and women are much more concerned about the future of their employment compared to the other European citizens. Overall, 14.6% of Greeks consider it “very” likely to lose their job in the next 3 months compared to the EU-27 average of 6.6%.

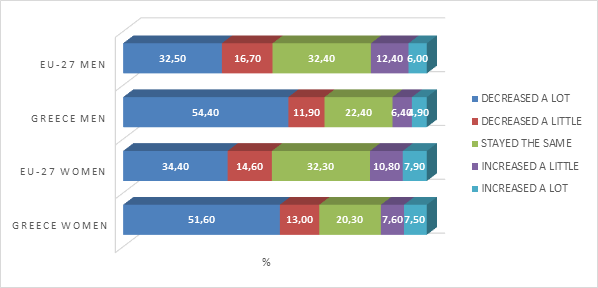

Although, as mentioned, the employment rates did not drop significantly during the first lockdown, the same did not apply for the working hours. This parameter was quite significant, as it may conceal a potential conversion of employment contracts from full-time to part-time work or employment by rotation, with a subsequent drop in wages.[8] According to the Eurofound data for Greece for April-May 2020, a smaller rate of women reported that their work hours decreased “a lot” compared to men, i.e. 51.6% for women as opposed to 54.4% for men.

Figure 3: Working hours during the pandemic, by gender, April-May 2020

Source: Eurofound (2020), Living, working and COVID-19 dataset, Dublin, http://eurofound.link/covid19data.

However, for both genders in Greece, the rates for decreased “a lot” working hours were much higher compared to the corresponding EU-27 average, where the difference was 22 percentage units for men and 17 for women. It is also interesting that a higher rate of women compared to men reported that their working hours increased “a lot”, 7.5% as opposed to 4.9%.

Working from home

The suspension of employment contracts and the universal lockdown during the first phase of extreme measures against the pandemic suddenly forced thousands of employees to work from home, in most cases through teleworking.

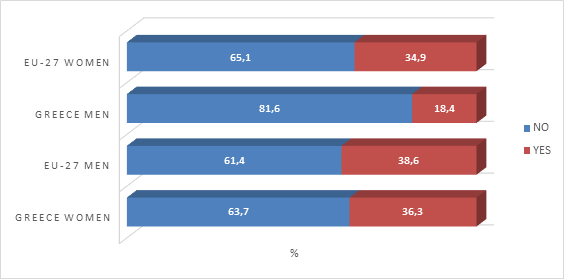

Figure 4: Working from home as a result of the pandemic, by gender, April-May 2020

Source: Eurofound (2020), Living, working and COVID-19 dataset, Dublin, http://eurofound.link/covid19data.

According to Eurofound data, women in Greece started working from home at a rate double than that of men, 36.3% compared to 18.4%, as a result of the pandemic. As a matter of fact, this rate is similar to the corresponding EU-27 average (38.6%). On the other hand, 81.6% of men reported that they did not work from home, when the corresponding EU-27 average was 65.1%.

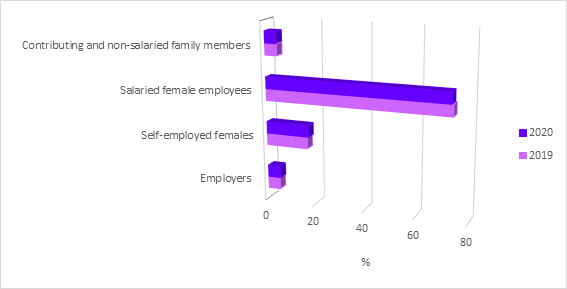

This difference in working from home rates between men and women may partly be explained by the fact that in Greece, women bore to a much greater extent the burden of caring for children and elderly family members, and running the household during the lockdown. Another reason may be that the majority of working women in 2019 and 2020 were salaried employees, at around 73%, followed by self-employed women at a much smaller rate of 17%. So they either continued to work from home or were placed on suspension from work. Female employers, as well as contributing and non-salaried family members, recorded low rates among female employees in total, with no significant change between 2019 and 2020.

Figure 5: Employed women per professional position, Q2 2019 & 2020

Source: ELSTAT, 2020

Closing remarks

What do we conclude from all this? It is strongly evident that during the implementation of the measures to address the health crisis in the first quarter, female employment in Greece proved resilient and, despite the ongoing inequalities in employment rates, it fared better than male employment. The most significant negative impact was the drop in female employment in tourism and catering activities. On the other hand, women make up the largest rate of healthcare employees, who are at the frontline of the pandemic, and employees burdened by educating a diversified population on lockdown!

However, the health crisis is continuing in full force and the measures taken to address it are creating even deeper rifts in the employment world, and are causing increased work and income uncertainly for the post-coronavirus era. In addition, thousands of women, invisible to the radars of the statistics surveys, such as domestic helpers, carers of elderly, patients and children, unregistered female employees working as dishwashers in shops that closed, and women in provision of personal services are sinking even further into poverty and exclusion.

So it is hard to know what the future holds for the job market, and especially registered and unregistered (i.e. unpaid) female employment, until we exit the pandemic, and beyond. It not only depends on the intensity and duration of the pandemic, but also on how the countries address it and the solidarity between them, on the priorities they set for the recovery, and on the choices they make to boost employment. In the end, it depends on the answers to the question hanging over our heads in the post-financial crisis era, irrespective of the pandemic, as to what kind of society and economy we want.

Bibliography

Alon T., Doepke M., J Olmstead-Rumsey J., and Tertilt M., (2020). Impact of the Covid-19

Crisis on Women’s Employment, in Econofact network, 27/08/2020

Vaiou N. (2020). “Stay home”: shrinking of the space and tiles of a tough daily routine.

In Kapola P., Kouzelis G., Konstantas O., (Eds) Reflections in precarious times / local 19th, Society for the Study of Human Sciences, Nissos Publications. www.nissos.gr

Del Boca, D., Oggero, Ν., Profeta, P and Rossi M.C (2020). “Women’s Work, Housework and

Childcare, before and during COVID-19”, IZA Discussion Paper No13409 Institute of Labor Economics (IZA). https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/13409/womens-work-housework-and-childcare-before-and-during-covid-19

EIGE Covid-19 and gender equality,

ELSTAT (2020). Press Release. Workforce Survey: Q2 2020

Eurofound (2020). Living, working and COVID-19, COVID-19 series, Publications Office of the

European Union, Luxembourg. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/data/covid-19

Kyriakoulias P., (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic. Impact on employment and work.

Internationally and in Greece. An initial review. Work and Employment, Thematic Bulletin National Institute of Labour and Human Resources (EIEAD), No. 1/2020

Kyriakoulias P., (2020). Teleworking in the EU before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Work and Employment, Thematic Bulletin National Institute of Labour and Human Resources (EIEAD), No. 3/2020

https://www.eiead.gr/publications/docs/EIEAD_THEMATIC__ISSUE_TELEWORK__FINAL. pdf

UN, COVID-19 and its economic toll on women: The story behind the numbers, Date:

Wednesday, September 16, 2020

UN WOMEN (2020). COVID-19 and Ending Violence Against Women and Girls

[1] And not just those. During the time of the COVID-19 lockdown, the incidents of domestic violence with women as victims increased dramatically, in some cases up to 30%. The UN Secretary-General, the Chair of the Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, the President of the independent body responsible for monitoring the implementation of the Council of Europe Istanbul Convention and the World Health Organization urged the governments to take immediate measures to prevent incidents of violence against women and support victims of violence during this time.

[2] The year when the 10-year economic crisis began, with extremely adverse consequences for the Greek job market.

[3] People placed on suspension of their contract continue to be considered employed, provided the duration of their suspension is less than 3 months or they receive more than 50% of their salary (ELSTAT, 2020), p.1

[4] Kyriakoulias P., (2020)

[5] ELSTAT 2019, 2020, Workforce Survey, Q2

[6] In “Human health and social work activities”, the majority of employees in Greece are women, at a rate of 66.24%, and the same applies for the crucial – and, as it turns out hard to manage, especially at the time of the pandemic – Education sector, where the employment rate of women is close to 65% of all employees

[7]Eurofound (2020). In April 2020, Eurofound launched a survey to record the impact of COVID-19 on the way people live and work in Europe. The survey was conducted online and included questions on the employment status of respondents, their professional life, the use of teleworking during the pandemic, their quality of life, their confidence in the institutions, etc. Concerns people aged 18-50+.

[8] See P. Kyriakoulias 2020, p. 10 and footnote 3 in this article.

-

Chrysa Paidousi

Chrysa Paidousi

Ph.D., Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, Greece